In the seventeenth century, the ideas propagated by the likes of the English philosopher, John Locke, made great impact in Europe. His social contract theory and the idea that men are born equal had tremendous resonance among the citizens who began to question the unlimited powers of their leaders. The old order began to disappear as people claimed more individual freedom and the absolute monarchies were replaced by parliamentary democracies. As people exercised their new found freedom of expression, the old practice of printing privileges and monopolies were challenged and the theory of intellectual property began to spread. The Stationers’ Company consequently set about to bring pressure on Parliament to grant some form of protection to authors and their publishers.

On January 11, 1709, a Bill was brought to the English House of Commons intended to pass a law “for the encouragement of learning, by vesting the copies of printed books in the authors or purchasers of such copies during times therein mentioned”. Arising from the draft Bill, a law was passed on April 10, 1710, with an introduction that said that printers had taken the liberty, without the consent of authors to print books and other writings, to the very great detriment of authors “and too often to the ruin of them and their family”. The law known as the Statute of Anne is widely believed to be the first copyright law in the world. It is the first known enactment recognizing the right of an individual to protect a published work, in the modern sense.

Before the Statute of Anne was enacted, there was massive exploitation of authors by printers who at that time were not required to obtain the consent of an author before embarking on the exploitation of his work. Strange as it may sound, the authors themselves did not have the right to publish their own books except they were members of the Stationers’ Company and obtained permission from the King, conditions which were most difficult to fulfill. The exploitation of the works of authors without their consent had dire consequences. Some of the most brilliant minds in England lived in penury. The situation discouraged gifted people from exploiting the resources of their intellect.

The stated objective of the Statute of Anne therefore was, “the encouragement of learned men to compose and write useful books”. The law gave the author of a book already printed the sole right of reprinting such a book for a term of twenty one years with effect from the date the law came into force. The author of a book not already in print or written was given the sole right of printing or reprinting the book for a term of fourteen years in the first instance. The author could renew the term for a further fourteen years if alive at the expiration of the first term.

The Statute of Anne only protected the authors of books. As the saying goes in Nigeria, the other classes of creators were on their own! Over time, even the protection given authors of books was criticized for being too limited. The law neither made any provision for the control of translations nor of public performance. Agitations for either new laws or changes in the existing law began to gather steam. The works of one of the most famous English cartoonists of the era, Hogarth was being massively reproduced. Hogarth, whose drawings always had a slant of biting sarcasm, became the arrow head of a movement that led to the enactment of the Engravers’ Act of 1735. The Act, for the first time, gave legal protection to the works of designers, artists and painters.

The development of the copyright concept in England coincided with the spread of the very powerful ideas of the French philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau. It was a very turbulent period in France as the revolutionary ideas of Rousseau flourished. The concept of literary property itself was revolutionary and quickly overthrew the system of privileges. In 1777, King Louis XVI promulgated six decrees which recognized the right of the author to control the publishing and sale of his work. During the revolution, attempts were made to remove all individual privileges and that of cities and provinces. At the end of the turbulence, a fundamental recognition was made by the French which in many ways might explain why the French have ever since, taken the lead on most issues related to copyright. The recognition was that the right of the author was not dependent on the concessions of public officers but on the natural order flowing from intellectual creation itself. France promulgated a decree in1791 which for the first time recognized the exclusive right of an author to control the performance of his work. Another decree of 1793 established another exclusive right of an author, the right of reproduction. The French also played a leading role in establishing the framework that produced the major international conventions on copyright.

Following developments in Europe, in the United States of America, most of the various states had some copyright provisions in their laws even before the American Revolution. For instance, the immortal words which proclaimed that there was “no property more peculiarly a man’s own than that which is produced by the labour of his mind”, came from the law passed by the state of Massachusetts on March 17, 1789, which provided protection for the works of authors. The first federal copyright law in the United States came barely a year after the Massachusetts law. The Copyright Law of 1790 provided for the protection of books, maps and charts. This was clearly in fulfillment of the powers given by the United States Constitution to Congress “to promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries”. Subsequent enactments however, appear to have given an elastic interpretation to the word, “writings” because these enactments went on to provide protection for dramatic performances, photographs, songs and other forms of art.

For most countries in Europe, the period following the enactment of the Statute of Anne, was a period of tremendous development in legislative affirmation of the author’s right. Some even did more than anyone could have hoped for. For instance, Norway and Denmark adopted an ordinance in 1741 which provided a perpetual exclusive right for an author or his heir. In Spain, King Charles III enacted a law in 1762 which emphasized that the privilege to print a book would only be granted to “the one who is the author”. It is reasonable to say that the fever quickly spread all over Europe, especially with the tremendous expansion of rights and the subsequent extension of such rights to foreign authors, which were all promoted by France.

In England, different statutes were enacted to increase the term of copyright and to bring more types of works other than books, to enjoy copyright protection. For example, an Act of 1842 provided that copyright will subsist throughout the life of the author of a book and for seven additional years after his death. Most of these statutes were combined to bring about the 1911 Copyright Act of England. The 1911 Act was extended to apply to the Protectorate of Northern and Southern Nigeria by an Order in Council. And then came the Nigerian Copyright Decree of 1970 and the immediate past Copyright Act of 1988 which this writer played no small part in getting enacted.

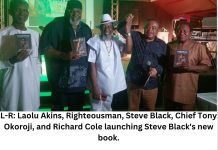

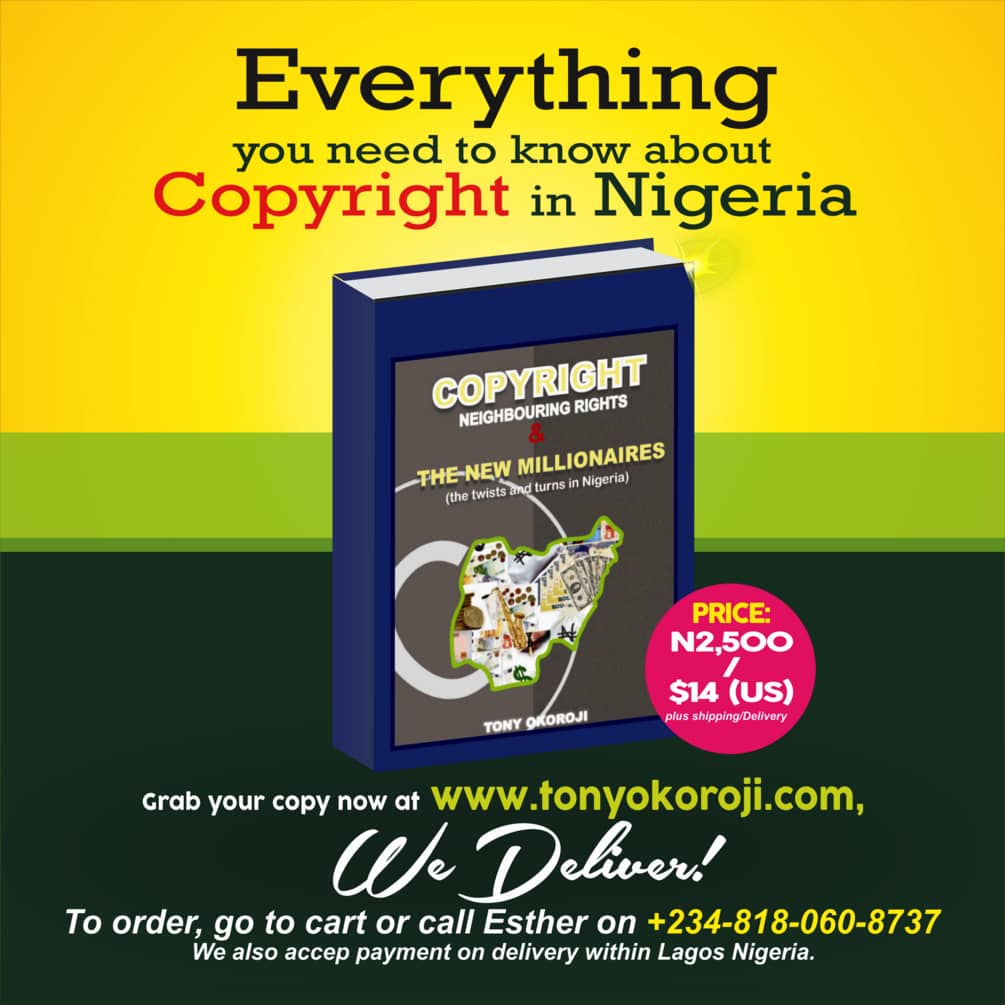

Today’s breakfast is an adaptation from my book, Copyright & the New Millionaires.